But the quality and sociotech movements invited people on the shop floor and in the back office to gradually improve their work together. Like the quality and sociotech movements, reengineering showed that business processes worked best when designed as a single, interrelated system. And its methods can, in fact, work miracles, especially in companies split into functional "stovepipes" and "silos," where R&D, marketing, and operations people have been isolated from one another. Process redesign is a nitty-gritty exercise in rethinking the flow of work and information. Hammer, Champy, and Davenport proposed were not very different from those of such old management luminaries as Russell Ackoff, Eric Trist (the theorist of sociotechnical systems), Joseph Juran, and W. Process redesign initiatives, of course, had existed on the management scene long before "reengineering" came along.

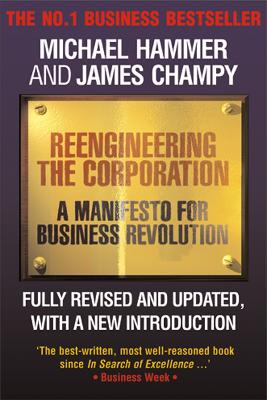

In that scant time hundreds of companies had leapt onto the bandwagon of BPR: the radical redesign of corporate processes (from order-taking to procurement, from product development to customer service) with the goal of dramatic breakthroughs in performance. Champy's book, Reengineering the Corporation: A Manifesto for Business Revolution, had become a runaway bestseller.

This was only eight years after they had coined the word "reengineering," and only three years after Dr. Beginning in 1995, the three most influential founders of business process reengineering (BPR) - former Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Michael Hammer, then-University of Texas professor Thomas Davenport, and James Champy, then-president of the consulting firm CSC Index - all issued public apologies. The management fad with the greatest reputation for arrogance is also the one most prone to mea culpas by its leaders.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)